By Megan Yoshioka

What was the driest sermon you ever heard preached in church? For me, it was a sermon I heard when I was in high school about the fruits of the Spirit. A very kind, knowledgeable pastor who looked to be in his 70s prepared a long, doctrinal analysis of each fruit. As much as I wanted and tried to be engaged with those important messages, I just couldn’t do it.

After church, I asked my mom what she thought of the sermon. She said it was different from what was usually preached, and she didn’t mind it. She said it was just “old school” and commented, “I haven’t heard a sermon like that in a long time.”

Apparently, different generations have different styles of ministry.

Southern Adventist University Religion Professor Elie Graterol has 17 years of pastoral experience in the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) church and has witnessed to many people of varying ages. Over the generations, he noticed a change in the effectiveness of different ministry approaches.

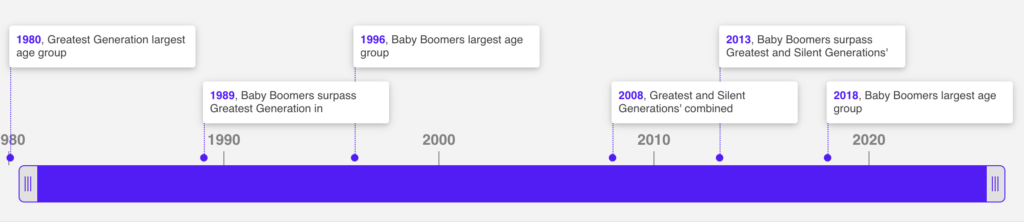

For older generations, such as the Baby Boomers, acceptance of religious doctrines precede church membership and involvement, according to Graterol. However, in order to witness to younger generations, he saw a need for method adjustment.

“For Millennials, it’s mainly, ‘Yeah, what the Bible says is cool,’ but that must be preceded by a very strong sense of fellowship and belonging,” Graterol said. “Fellowship and belonging will open the door for a Millennial to embrace the Bible. In the past, it was the opposite. The Bible opened the door for a Boomer to belong in that particular group or church.”

Interning Pastor Xavier Baca also recognizes relationship building as an effective ministry tool. Baca has been interning for the Wahiawa and Waimanalo SDA Churches in Oahu, Hawaii, since August of 2020. Although most of his experience has been witnessing to younger people, he found a common denominator across all ages regarding ministry.

“I think the most important aspect, no matter what age, is giving people an experience with God,” Baca said. “If people have no experience with God in any type of religious activities or social gatherings in church, then it’s going to be harder for them to want to stay in a Christian church.”

Baca found that building relationships with others is a successful way to help people experience God. He explained that once somebody forms a connection with another person, it allows that person to be an influence for God.

“Once that relationship is built up, then I truly believe that the influence can be put in,” Baca said.

In regard to witnessing to any generation, Graterol also emphasized the importance of maintaining a strong connection with God.

“When you are connected with the Spirit, you will attract people,” Graterol said. “If you are a genuine Christian, you will earn the respect of all the generations, regardless of their perspective and worldviews.”